Observer Memory and Imagination as our Inner Social Lab

Ying-Tung Lin (National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University)

Episodic memory allows us to mentally travel back to the past, while imagination transports us to hypothetical, future, or fictional scenarios. For example, we can remember our first romantic date or the dinner from yesterday, and we can also imagine how a past conversation might have gone if we had said something differently, what the next trip will be like, or what it would feel like to become a vampire.

Such mental activity appears rather individualistic: It concerns only one traveler mentally traveling. However, I propose that examining social aspects of observer-perspective episodic memory and imagination reveals intriguing similarities between these processes and mindreading, which refers to the ability to attribute mental states to others.

The idea that memory, imagination, and mindreading are linked is not new. For instance, Buckner and Carroll (2007) suggested that similar neural mechanisms are involved across these cognitive processes, which they called self-projection. Shanton and Goldman (2010) drew from the simulation theory of mindreading, which suggests that we make sense of others by mentally simulating them within ourselves, to argue that mindreading, episodic memory, and prospection share the same type of simulation mechanism.

In addition, while Addis (2020) focuses on arguing that memory and imagination are fundamentally the same process, the simulation system she proposes, which allows for the “mental” rendering of experiences, also underlies other types of cognition, such as theory of mind, beyond mental time travel.1 Recently, at the Simulationism workshop in 2023, Nazim Keven proposed a radical continuist view within a simulationist framework, suggesting that memory, imagination, and mindreading differ only in degree, not in kind.

Here, I highlight how examining observer perspective memory and imagination and various forms of self-identification in these experiences can shed light on the connections between memory, imagination, and mindreading.

Observer memory, which allows an individual to see an event from an external viewpoint, has been studied extensively in psychology (Nigro & Neisser, 1983; Rice, 2010; St. Jacques, 2024; Sutin & Robins, 2008). When adopting an observer perspective, one’s first-person perspective—i.e., the origin of a visuospatial model of reality—and the represented body are dissociated from each other. In philosophy, it is debated whether this form of memory constitutes genuine or accurate memory (Dranseika et al., 2021; McCarroll, 2018; Sutton, 2010). Observer perspectives are also found in imagination and dreams (Rosen & Sutton, 2013).

An intriguing aspect of observer memory and imagination concerns how self-consciousness is understood in these scenarios. Self-consciousness is crucial for mental time travel, enabling individuals to “travel” and experience the protagonist as the same person across different times or worlds.

When the visual perspective is separated from the represented body, how does self-consciousness manifest in such scenarios? How does one identify with oneself in observer-perspective experiences?

Several identification patterns may emerge (see Figure 1): identifying with the observer's viewpoint (A), with the protagonist/represented body (B), with both (A and B), or shifting between the two (between A and B).

In the context of observer memory, McCarroll (2018) argues for the identification with the protagonist (B). In his view, because one did not see oneself at the time of the past event, the observer perspective is best understood as involving an unoccupied point of view—that is, the scene is merely presented from a certain point of view without any experiencer occupying and viewing the scene from that detached perspective. Conversely, I advocate for the identification with both the viewpoint and the protagonist, for it provides the most coherent explanation of how subjects describe their experiences (Lin, 2018, 2020).

To address the issue of self-identification in observer-perspective experiences, Vilius Dranseika and I conducted an experimental philosophy study to explore self-representation in observer-perspective imagination (Lin & Dranseika, 2021). Participants were asked to imagine running on a deserted beach from an external viewpoint and to choose which of the following best describes their experience.

[1] It feels like I am the one observing the scene from an external vantage point.

[2] It feels like I am the one inside the scene (i.e., the person [running on a deserted beach]).

[3] It feels like I am both the one observing the scene and the one inside the scene at the same time.

[4] It feels like I am switching between being the one observing the scene and the one inside the scene.

We found that approximately half of the participants identified with the one observing the scene [1]; a quarter of participants chose the option of identifying with both the one observing the scene and the one inside the scene [3]; only a small number of participants identified with the one inside the scene [2] and [4] (see Figure 2).

Our results seem to suggest that the identification is rarely dissociated from the observer perspective in imagination and that first-person perspective is a strong attractor for self-consciousness in imagination. Note that we conducted the study in observer imagination, and so it did not directly resolve the debate on observer memory mentioned above.

However, even in observer imagination, I think this conclusion is far from definitive. I speculate that many different factors could influence the results. For instance, if participants were asked to mentally practice a physical exercise such as playing tennis (Dana & Gozalzadeh, 2017) in which embodied components are more likely to be involved in the imagination, perhaps more people would identify with the protagonist inside the scene [2] instead of the one observing [1]. This speculation suggests that, in addition to our flexibility to switch between field and observer perspectives in memory and imagination, there may also be flexibility in switching self-identification within an observer perspective mental episode.

Moreover, social factors might also play significant roles here. When adopting an observer perspective, the self could be represented differently depending on the social context (see Figure 3).

For example, when recalling an event where I embarrassed myself in public, I can simulate how others might see me by self-identifying with an observer viewpoint, as if I had been one of the (potential) bystanders watching this person embarrass herself. This could be a way for individuals to react to such social situations: in some cases, adopting an observer perspective in this way to remember the past can lead to a more distanced and less emotionally charged response (ii).

However, I might also find that same embarrassing event as a fun story to share with friends, and when recounting the story, I might focus on what I did and how I felt under others’ gaze and attention. In such cases, I hypothesize that we are more likely to represent ourselves where the protagonist is, treating the observer perspective as others’ perspective (iii). This might be how we can feel more self-aware even when remembering with an observer perspective. I suggest there is flexibility in how we can represent ourselves in an observer perspective memory and imagination, influenced by various factors, including social factors.

These two forms of observer perspective with different self-identification may offer different pieces of social information. In her book The Space Between: How Empathy Really Works, Heidi Maibom (2022) summarizes various forms of actor-observer asymmetries found by Malle and his colleagues to argue that adopting more subjective viewpoints can lead to less biased and partial view of things. The asymmetries between “how we think of ourselves as actors” and “how we think of others as observers” (p. 68). These include how we systematically differ in describing and explaining our and others’ actions—for example, whether we mark beliefs as such in explanations, whether we adopt reason explanations or causal-historical explanations, the types of reasons we give, and how much attention we pay to experiences, etc.

I suggest that these two forms of observer-perspective experience enable us to learn how we see ourselves as observers (ii) and how others see us as observers (iii), as well as the discrepancies with how we see ourselves as agents (i) and how others see themselves as agents (iv).

The illustration of these forms of self-representation in observer perspective experience and their social dimensions seeks to demonstrate how memory, imagination, and mindreading may be interconnected. In observer memory and imagination, where the perspective is dissociated from the protagonist or represented body, a type of social-like relationship is facilitated.

This allows individuals to choose which one to “stand by” and from which to distance themselves. From the other angle, the observer perspective experience in which one identifies with the represented protagonist can perhaps be regarded as a variant of mindreading—a specific type in which the object is oneself.

As I examine various forms of observer memory and imagination and their similarities with mindreading, it shows that memory and imagination do not merely take us on a mental time travel journey but also to a social event where we meet and/or are met by ourselves. An observer perspective experience can be used as an inner social lab, allowing us to simulate the outer social world.2

I am grateful to Nazim Keven for directing my attention to these works.

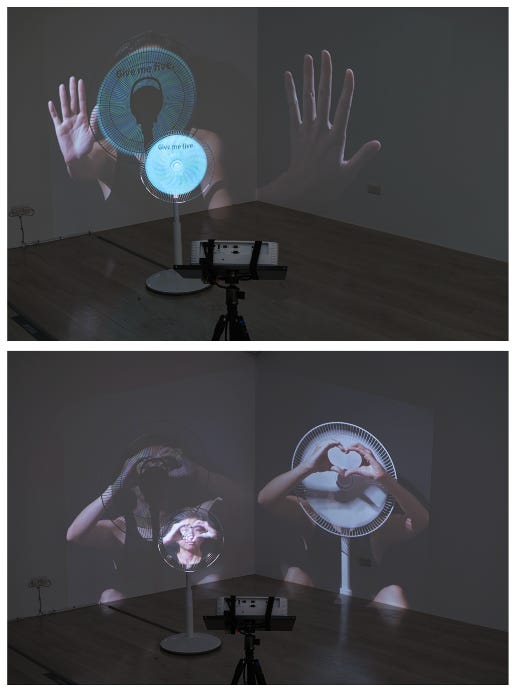

I would like to thank Chris McCarroll, Vilius Dranseika, Marta Caravà, and Sarah Robins for their feedback on this blog post and Pei-Yao Lin for the photos, including the cover photo, which is from her piece “Two-faced” (2022).