The Error That Lies: How Teleosemantics Illuminates Memory and Confabulation

Krystyna Bielecka (Institute of Philosophy, University of Białystok)

Memory is not a faithful diary of past events. Instead, it is a dynamic narrative —a channel of communication where information flows between our inner minds and the world around us. In this post, I want to share my teleosemantic account of memory, illustrated through cases of confabulation in Korsakoff’s syndrome. I also look forward to sharing more ideas in my forthcoming book with Springer, titled What is Misrepresentation?

Memory as a Communication Channel

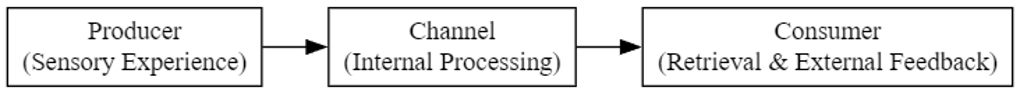

Imagine memory as a network where experiences are first “produced” by our minds and later “consumed” both by our inner error-checking systems and by those around us — friends, family, or clinicians. In this picture, encoding an everyday experience is like creating a message. But unlike a perfectly recorded note, this message is subject to distortion. My teleosemantic framework examines how and why these errors occur.

Memory is not simply a record of the past, but a dynamic narrative co-created by our minds and social interactions.

Teleosemantics studies of how our memories gain meaning through biological functions. In this view, a key component of any mental representation is the capacity to spot when an error has occurred. Just as a GPS recalculates a route when you miss a turn, our mind needs a built-in error detection system to ensure that what we remember corresponds to what actually happened. When this system fails or is compromised — as in some cases of neurological damage —our memory can produce confabulations: memories that sound plausible but are not accurate reflections of our past.

Confabulation Illustrated: Lessons from Korsakoff’s Syndrome

Korsakoff’s syndrome (KS) provides a dramatic window into what happens when memory goes awry. Typically caused by severe thiamine deficiency and often linked with long-term alcohol misuse, KS damages the brain’s ability to form and retrieve accurate episodic memories. Patients with KS might be unaware of their memory loss and unconsciously fill in the gaps with invented details.

Let’s consider two illustrative cases.

Patient C.A.: C.A. is a 67-year-old woman who experienced severe memory disturbances after a period of heavy drinking and poor nutrition. When questioned about her whereabouts, she often provided conflicting answers —sometimes claiming she was at home, other times stating she was simply visiting a friend in the hospital. Her confabulations emerged only when the interviewer probed specific details. This shows that, even when the cognitive system is still, partially functioning, a failure in error detection can lead to alternative narratives filling in for missing memories.

Mr. Thompson: Mr. Thompson’s case, described in the famous work of Oliver Sacks, shows another aspect of confabulation. When interacting with hospital staff, he would contradict his surroundings by mixing up identities and contexts. One moment he might refer to the doctor’s coat as belonging to a butcher from next door. Despite obvious discrepancies, he would promptly agree when corrected. This scenario underscores how, even if brief feedback adjusts the narrative, the underlying error-detection mechanism remains hampered.

The Teleosemantic Model of Memory

At the heart of my account there is the idea that memory acts as a channel that communicates experiences. This channel involves three basic stages.

Producer Stage: Here, sensory experiences and events are encoded as memory traces. Think of this like playing the first note in an orchestra.

Channel Stage: Over time, these traces may degrade due to natural decay or interference. In our daily lives, distractions and time itself introduce “noise” into the signal.

Consumer Stage: Finally, the stored memory is “retrieved” by internal evaluative systems and even by external agents — such as conversations with friends or questions posed by a doctor. These consumers check the coherence and accuracy of the memory.

When one part of this chain fails — especially the error-detection mechanism in the consumer stage — confabulations occur. Instead of recognizing a gap or inconsistency in their recollection, the patient’s mind constructs a plausible but false narrative.

Our minds act as both storytellers and critics. When the critic is absent or impaired, the storyteller runs amok.

In healthy memory processes, external cues (such as feedback from others) can help signal when a memory might be off track. For instance, if a family member notices that details in a recalled story seem out of place, they may gently challenge the narrative. This interaction acts as a corrective mechanism. However, in cases like KS, even when someone points out the inconsistencies, the patient’s internal error-checking may not function strongly enough to revise the memory in real time.

Beyond the Individual: Memory as Distributed Cognition

Traditional accounts of memory often focus solely on individual cognitive systems. But a teleosemantic perspective reminds us of the social dimension of memory. Our recollections are not assembled in isolation; rather, they are continuously shaped by interactions with others. In therapeutic settings, for example, caregivers and doctors serve as external consumers who provide corrective feedback. This not only helps to validate or challenge the patient’s narrative but also plays a role in re-establishing a connection with actual events.

When we consider memory as an emergent property of both internal processes and external interactions, it becomes easier to grasp how errors — and the confabulations that stem from them — might arise. In essence, the very process of communicating our memories creates spaces where misrepresentation is possible. And it is within these spaces that the error-based teleosemantic approach finds its strength.

Navigating the Complexity of Memory Errors

That memory is error-prone is a natural side effect of a system that is built to be adaptive. Our brain constantly negotiates a trade-off between accuracy and applicability. A system that rigidly adheres to a “perfect record” might be too inflexible to guide everyday decision-making.

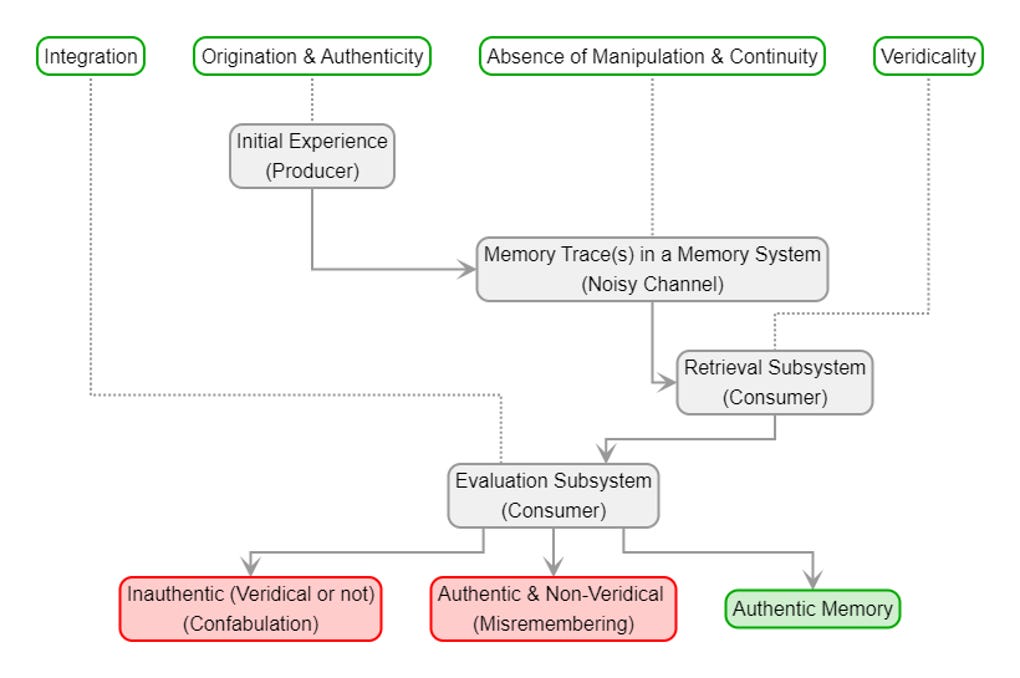

In the teleosemantic view, ensuring that memory is both accurate and useful involves several conditions.

Origination: The memory should stem from one’s own lived experiences.

Authenticity: It should accurately reflect the individual’s personal viewpoint during the original event.

Veridicality: The memory ought to correspond with objective reality.

Absence of External Manipulation: It should be free from distortions imposed by external forces.

Continuity of Memory Trace: There needs to be an unbroken chain linking past experience to the present recollection.

When these conditions are not met — even one of them — the system is prone to confabulation. In patients with KS or similar conditions, defective error-detection signals that these conditions are not met. The result is a memory that is inauthentic or only partially accurate.

Why a Teleosemantic Account Matters

The advantage of viewing memory from a teleosemantic perspective is that it provides clear heuristics for understanding where errors can arise. Instead of simply labeling a patient’s incorrect memory as “false,” this approach asks critical questions: Who is responsible for detecting an error in the memory? Has the feedback from the environment (such as from a caregiver) been integrated into the recollection? Is the system truly capable of correcting itself? By answering these questions, we gain a more nuanced view of why some memories are confabulated and others are merely misremembered.

Moreover, this account shows that the cognitive architecture underlying memory is not limited by the individual alone. It is a distributed process — one in which even social partners can sometimes be part of the error-checking system. This broader perspective points toward new directions for empirical research and therapeutic interventions, especially for conditions like KS.

Reflections on Misrepresentation

In my forthcoming book, What is Misrepresentation? , I develop the idea that epistemic accuracy is what minds care about. Cognitive systems rely on complex devices to check for coherence between these representations. Misrepresentation is not simply a mistake; it is, in many ways, a feature of our cognitive architecture. By understanding the conditions under which misrepresentation occurs, we can learn more about the strengths and weaknesses of human memory.

Errors are not just flaws; they are windows into how our minds work.

Viewing memory through the lens of teleosemantics reframes confabulation from being a mere symptom of neurological damage to a signal that our brains rely on error-detection systems — systems that sometimes fail. When these failures occur, the narrative we construct about our past can stray dangerously far from what actually happened. But even these errors offer insight. They remind us that our memories are shaped not only by the events themselves, but by the continual interplay between our inner thoughts and the external world.

Concluding Thoughts

The teleosemantic theory of memory bridges the gap between our inner cognitive processes and the external social world. In situations like Korsakoff’s syndrome, where false memories run rampant, this approach helps explain why and how these errors persist. By emphasizing the importance of spotting mistakes and getting constant feedback — from inside our minds and the world around us — we uncover valuable insights into the delicate and captivating nature of human memory.