"She's not dead, is she?" Risk-Taking, Agency, & the Politics of Traumatic Memory

Em Walsh (University of Central Florida)

Imagine that the person you have loved most in the world has passed away recently. You cannot bear the emotional pain caused by their loss. You see an advert suggesting you could divide your memories between work and personal life. You calculate that this means that you will only have to endure the pain of your grief for part of the day, as opposed to all day.

Would you opt to have your memories severed to avoid the pain of your grief, at least for part of the day?

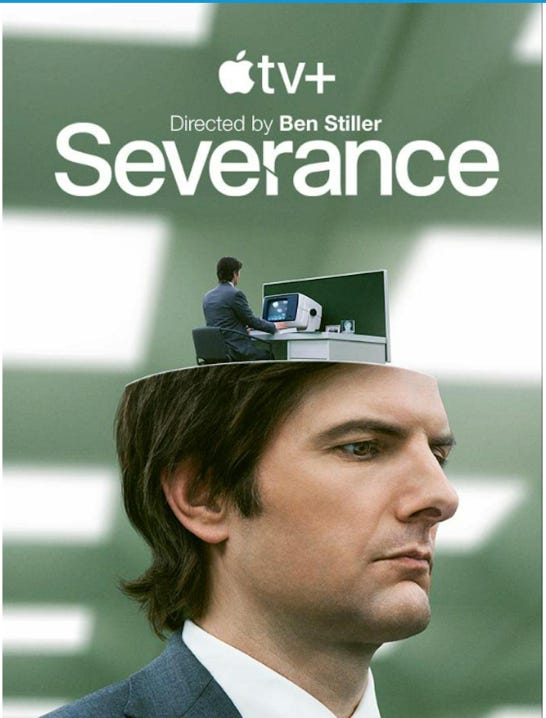

In the TV show Severance , some do that. The show’s premise is that one can consent to the procedure of severance as described above: one can have their memories “split” between work and personal lives. After the procedure, one has an “innie” – their work-life memory – and an “outie” – their personal life memory. Basically, two different selves. Communication between these selves appears impossible, although this is challenged as the series unfolds.

As the show depicts, those who have consented to severance have no sense of how they spend their time in “outie” mode whilst in “innie” mode. Whilst outside of work, they have no sense of who they work with, whether they like their job, or what they even do at their job. Imagine! You cannot answer questions about what you do and whether you are proud of it. You cannot recall that your co-worker Paul is a know-it-all and that your co-worker Jane is like your sister. You live two entirely separate lives with separate selves.

Now, I pre-empt that many of you will bark at the idea that someone would consent to such a procedure even if it could be performed. But the question “why would one consent to such an invasive and undesirable procedure?” is precisely what is interesting in the show, especially for me as a researcher who has been interested in how traumatic memory makes one feel stuck in the past.

The show depicts that the motivations of consenting to severance for at least one character in the show, Mark, are impacted by traumatic memories, as Mark signed up for severance to escape from the traumatic memory of his wife's death caused by a car accident.

What about traumatic memory makes one liable to take risks in this way?

Trauma researchers have shown that those with a history of trauma will often engage in risk-taking behaviors, even with severe personal consequences. Part of the behavioral explanation lies at the neurocognitive level and the way traumatic memory interferes with the ordinary operations of the default mode network, as trauma impairs self-awareness whilst simultaneously causing an individual to become preoccupied with trauma-related stimuli.

We can see this clearly in how Mark is depicted in the show. He exhibits little concern for either of his selves (work or personal) but an incredible preoccupation with avoiding having to think about his wife's death. Traumatic experiences make people less preoccupied with their sense of self and more preoccupied with preventing trauma stimuli.

Of course, the neurocognitive story is only part of the explanation, as with all instances of psychic distress. Another level of explanation is found at the emotional level. As Frijda's work on emotions shows, if there is no emotional closure regarding a particular event, its emotional load will often haunt the individual attempting to escape it.

This emotional load is particularly poignant in the context of traumatic experience and grief. Distinguished researchers on grief have shown that grief alienates a person from themselves and the world around them. Adopting a relational framework of alienation, Køster shows that grief alienates an individual because their world no longer makes sense as it did before. Here he explains how a bereft partner may experience their living space while grieving.

My daily routines, such as making coffee, setting the table for two, grocery shopping, etc., have become superfluous in their current form. Her things that surround me…have lost their animation and are now rather intrusive on experience because they now point to the emptiness she left behind…My connection to the habitual world that sustains me has become a relation of relationlessness, of feeling alienated. This is the existential meaning of statements such as… “losing her is like losing a part of my self”.

Exciting recent work in philosophy of memory examines this phenomenon in the context of transgenerational trauma, showing that Shoah survivors are essentially “stuck in grief” because their habits of alienation are passed down generationally through mimetic repetitional behaviour.

So far, the picture I have painted as to why Mark signed up to severance are bleak. He is more focused on avoiding trauma stimuli than he is on the importance of his sense of self: he suffers from a ruptured sense of self given the alienation caused by the loss of his wife and his inability to emotionally process this.

But this negative picture of why a traumatized individual like Mark may have signed up for severance is not the whole picture. The positive part of the picture as to why traumatized individuals take risks has to do with regaining their agency.

Narrative reports highlight this connection between agency and risk-taking in the context of traumatic experience. Here is one such report by an individual with severe developmental trauma, who took up shoplifting as a means of regaining agency.

“I started shoplifting when I was five. I’d pretend to add the quarter my mother gave me to my collection plate, then sink it deep and hot into the pocket of my Sunday dress. On the long walk home, I’d pass a pharmacy where I'd steal a Clark bar or a Milky Way, pantomime leaving the quarter for my coke and with a mix of terror and thrill leave the store, sugar happy and known to myself…I shoplifted well into my adulthood, at great risk to me were I to be caught… It was always confusing why I did this. It was so, so risky. I knew that. But, I think the adrenaline organized me, rising it seemed from my belly through my brain, from the back to the front. I felt my feet; I knew my hands and fingers; I had eyes. I was agency. It lit me up.”

Here lies the tragedy of trauma. To counteract the negative effects of trauma, without adequate social support, there is only one option to regain agency – to take risks. Risk-taking reactivates the areas of the brain that have become dull due to the traumatic experience itself.

We see this in recent work on other areas of psychic distress, such as depression. Recent work in bioethics identifies individuals with severe depression opt for deep brain stimulation, an irreversible and invasive procedure when they feel they have nothing left to lose.

Perhaps, in idealistic societies that did not exploit personal vulnerabilities, we would not have to be concerned about the picture I have painted so far concerning the connection between risk-taking and agency in the context of traumatic memory. But we do not live in ideal societies.

Severance lays this out clearly for us all to see. And, in so doing, it teaches us important lessons about the socially and culturally mediated nature of memory and its relevance to politics.

Those who consent to severance are traumatized and sign up for a multitude of reasons, only to realize the stomach-churning lesson that ghosts can't be buried but you can bury yourself in the process. Governments based on principles of domination rarely act in protection of the most vulnerable in society and instead tend to exploit these vulnerabilities in opaque ways that may cause individuals to consent to self-mutilation in times of psychic distress.

When traumatized individuals do take the risks presented to them, even when socially encouraged to do so, they are often villainized in ways that make their actions seem erratic and illogical.

"Do you ever think the way to deal with a fucked-up event in your life isn't to shut your brain off half the time" (Severance, episode 4)

As memory researchers have shown, social and cultural norms control how we remember and what we forget. I suggest that these norms similarly influence the stories we tell about how erratic and illogical traumatized individuals are for engaging in risk-taking behavior.

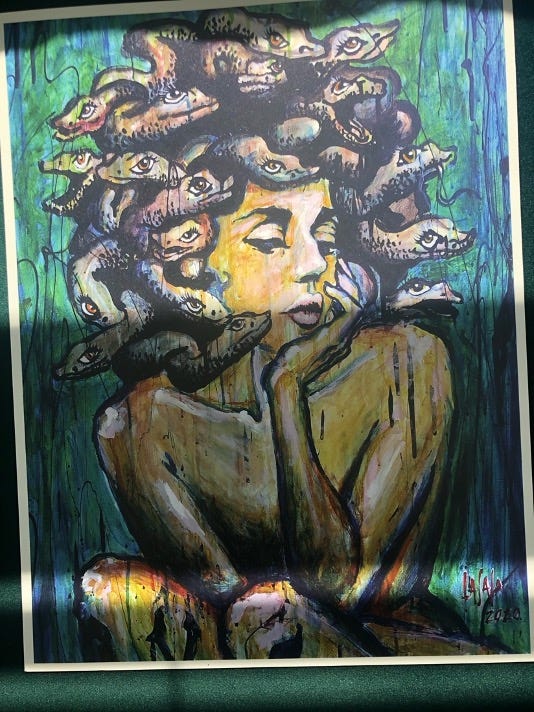

Just like Medusa was blamed and shamed for her rage after her abuse, we blame and shame traumatized individuals for taking risks rather than asking the critical question of what caused them to want to take the risk in the first place. In so doing, we fail to see the full picture of why risk-taking is so tempting in the aftermath of a traumatic experience.

I hope to have shown that we should be slower to criticize individual actions and faster to pay attention to the social spheres that may exploit the connection between risk-taking and agency in the politics of traumatic memory.

This post is dedicated to a brilliant student of mine, Emily Schuster, who recommended the show Severance to me and all who have had to engage in risk-taking behavior to regain a sense of agency after a traumatic experience.

Interestingly, I just started watching Severence. I am on the second season and have so many thoughts - some about the psychology and others philosophical.... Very interesting, educational, thought-provoking.