Nostalgia has come a long way. In sharp distinction to how it was historically conceived as a deadly disease to be treated in medical terms, nostalgia is today more likely thought of as either a harmless mode of self-indulgence or otherwise a resource for well-being and the production of meaning. To give but one example, in a recent book by well-known exponent of the new nostalgia, we read how nostalgia can benefit us in terms of building healthy self-esteem, expanding selfhood, connecting us to others, and building a better future.

While nostalgia’s transformation is complex, spanning numerous disciplines over different generations, there can be little doubt that research in empirical psychology, to say nothing of Covid-19 related nostalgia, is partly responsible for the reinvention of nostalgia in our own era.

This reinvention of nostalgia as a mode of self-help therapy extends to themes related to death and grief. Alongside supposedly buffering anxieties tied up with death, nostalgia is also thought of as being a resource for individuals experiencing bereavement. Nostalgia achieves this, so the argument proceeds, by supposedly acting “as a corrective mechanism to alleviate the negative impact of adverse events” such that, “nostalgia serves a restorative function, helping individuals higher on it to re-establish psychological homeostasis in the aftermath of distress.”

As appealing as this prospect may be, much of the psychological research on nostalgia relies on a circumspect and reductive account of the emotion. In particular, contemporary ideas of nostalgia often frame the past as a storehouse of memories passively awaiting recollection, presuppose personal identity as being continuous and self-identical, treat nostalgia as a resource that can be deployed in a pre-emptive manner for future uncertainties, neglect the role unconscious processes play in the production of nostalgia, and ignore the affective dissonance between past and present central to nostalgia (cf. Routledge 2016).

Furthermore, we find almost nothing on variations of nostalgia, such as pathological articulations of nostalgia or nostalgia conceived of as a temporally extended process rather than a short-term episode. Worse still, throughout this research, nostalgia’s affective ambiguity has been stripped of its complexity, with a prevailing focus on the role nostalgia can play in generating pleasure rather than recognising how it can lead to suffering.

The result is that nostalgia is deprived of both its richness and also its historical importance. After all, etymologically the term “nostalgia” derives from “nostos” meaning (return to the homeland) compounded with “algos” meaning suffering or grief, as Johannes Hofer, the founder of the term, writes, “the grief for the lost charm of the Native Land” (Hofer 1934, 380). And yet, in contemporary research on nostalgia, grief is almost nowhere to be seen.

While grief is generally missing in current nostalgia studies, contemporary grief research, especially within phenomenology, evinces a more astute attention to issues of nostalgia and memory. Thinkers such as Matthew Ratcliffe, Allan Køster, Thomas Fuchs, and Line Ryberg Ingerslev all point toward the role pastness and nostalgia play in the experience of grief.

Within this field of research, grief is understood as having a complex intentional structure, irreducible to a short-term affective state and instead grasped as a temporally-extended process, with a wide range of expressions and durations. Grief is also conceived in bodily terms as a specific kind of felt pressure in the body, which is articulated as episodic moments of acute pain when the loss is confronted and which is otherwise diffused through the body as a felt sense of lack.

Current research also underscores how the bodily experience of grief attests to the intertwinement of self and other. Seen in this way, the body is the vehicle of expression for the intertwinement of self and other in a jointly constituted world, pointing toward a shared history which is no longer accessible. This history, moreover, is taken up in the surrounding world, such that the familiar if not homely world once inhabited in turns becomes alienating and empty after the death of the loved one.

One of the recurring motifs in the literature on grief is that the experience of loss does not always result in the experience of unequivocal absence, but instead establishes the space for the past to present itself as an ambiguous presence.

The term “ambiguous presence” refers to the knowledge that a loved one is dead but nevertheless present to the grieving subject as if they were still here.

In this respect, their presence marks an affective and epistemic conflict, such that there is a dissonance between what one rationally grasps as true—namely, that the loved one is dead—and what nevertheless continues to be felt in an equally compelling fashion—namely, that their presence is felt as though they were still alive.

The literature on grief is populated with such spectral revenants. Consider here Denise Riley’s incisive set of reflections on the death of her son. What marks this writing is a joint conviction of knowing but not believing that her son is dead compounded with the sense of time as being coming to a standstill: “Knowing and also not knowing that he is dead. Or I ‘know’ it but privately I can’t feel it to be so…Half realizing while half doubting, assenting while demurring, conceding while finding it ludicrously implausible” (Riley 2019, 107).

There are a number of ways we might think about this double bind between knowing and not knowing. We could, in the first instance, think about the tension in terms of a “delusion.” But to do so would risk overlooking the ways in which phantoms and presences enable us to maintain a meaningful relation to a past that is no longer accessible. The same is no less true of nostalgia. In nostalgia, phantoms also play a key role not only in terms of connecting us with worlds that are no longer available, but also in terms of generating an atmosphere of familiarity in an otherwise unfamiliar world.

Seen in this way, both the nostalgic and grieving subject inhabit divergent modes of affect, temporality, spatiality, and identity concurrently. For each of them, living in the present means dwelling in a zone of time that is shaped by the past, and indeed, only made meaningful with recourse to the past. Another way to think of this state is in terms of doubling of worlds. In her seminal work on the topic, Svetlana Boym notes that:

A cinematic image of nostalgia is a double exposure, or a superimposition of two images—of home and abroad, past and present, dream and everyday life. The moment we try to force it into a single image, it breaks the frame or burns the surface (Boym 2001, xiii-xiv).

Boym draws our attention to the duplicity at the heart of nostalgic longing. If nostalgia involves a “longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed,” then any such longing serves less to unify disparate worlds and more to generate a doubling of these worlds. Boym’s reference to a “double exposure” thus attests to the difference inherent to nostalgia. As a double exposure, nostalgia implicates a joint structure, where the irretrievability and felt quality of the past as “longer exists or has never existed” is grasped from the standpoint of a still living subject. No longer being present does not, however, mark a concession to the expiration of the past; rather, it underscores how the persistence of the past is articulated in terms of the felt difference within the subject.

Like grief, the nostalgic subject forges a world that is structured by the division of time, the result of which is a partial separation from common time. Common time—the shared time of the social world—is never fully dissolved in nostalgic phantasy; rather it assumes a tacit presence, at times encroaching upon nostalgic longing and at other times fading into the background.

Because of this blurring of divergent temporalities, the familiar glow of pastness is offset by the contemporality of a present from which that past is conceived. In turn, this temporal warping generates a specific kind of ambient affectivity, which is marked by a mood of temporal protraction and lassitude. Time, as Denise Riley has it, becomes a plateau. And the past, such as it is, folds over into the present saturating the perceptual horizon with the tonality of an experience that was once lived but never realised.

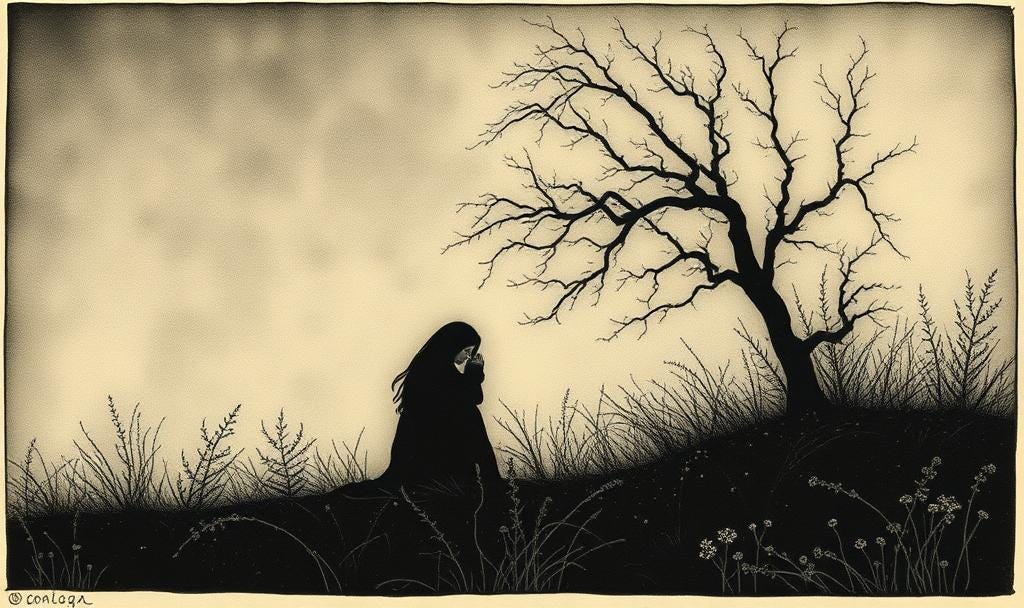

In both nostalgia and grief, the world can appear for us alien, unhomely, and deprived of the meaning it once assumed.

While it might seem self-evident that grief involves a fundamental fragmentation of the world, to phrase nostalgia in the same fashion, on the other hand, seems counter intuitive at first glance. Yet I would argue that this response is symptomatic of the trivialisation of nostalgia, carried out in large by work in empirical psychology. Far from simply being “beneficial” to the grief process, as contemporary psychological research would have it, I would instead posit that nostalgia is better grasped as a modality of grief, which is irreducible to a longing for specific things, but instead taken up in the loss of the (home)world from which those things belong.

References

Boym, Svetlana. 2001. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

Hofer, Johannes. 1934 ([1688]). “Medical dissertation on nostalgia or homesickness.” Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 2: 376–391.

Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Short, S. D., Willis, K. D., Moloney, J. M., Collison, E. A., Gramling, S. (2020). “The past as a resource for the bereaved: nostalgia predicts declines in distress.” Cognition and Emotion, 35(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1825339

Reily, Denise. Say Something Back and Time Lived, Without its Flow. London: Picador

Routledge, Clay. 2016. Nostalgia: a Psychological Resource. London: Routledge.

Routledge, Clay. 2023 Past Forward: How Nostalgia Can Help You Live a More Meaningful Life. Colorado: Sounds True Publishing.