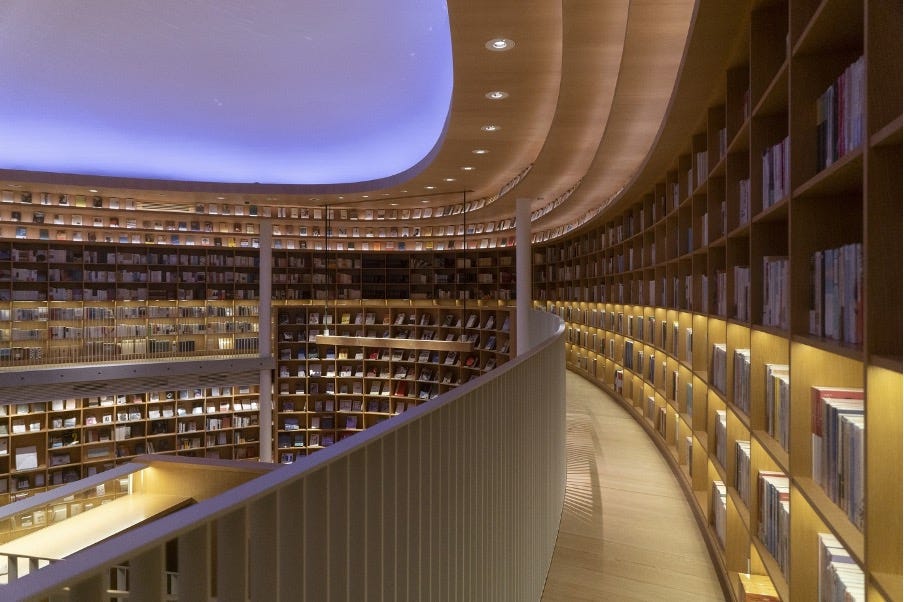

We live in the age of the storytelling boom. Self-narratives sell big in the attentional and emotional storytelling economy. Online and offline, in conversation and in writing, self-narratives are everywhere. From talk shows to memoirs, from podcasts to social media posts. Self-narration also features prominently in our everyday conversations amongst family members, partners, and friends. Everybody has a story to tell about themselves and their past, everybody seeks to get their story straight.

Philosophical research suggests that self-narration can be conducive to self-knowledge and social understanding. And research in developmental psychology indicates that self-narrative practices play an important role for the development and cultivation of autobiographical remembering. Through self-narration, all of this suggests, we can engage in exercises of meaning-making, interpretation, and revision as we navigate and negotiate our personal past.

But what exactly is the relationship between self-narration and autobiographical remembering?

For current purposes, I define autobiographical remembering as the process of re-actualising facts (the semantic component) and events or experiences (the episodic component) that are relevant for relating to one’s personal past. Autobiographical memories are the products of processes of autobiographical remembering.

Recently, Richard Heersmink developed an account according to which autobiographical memories are the “building blocks” of our self-narratives. On this account, the purpose of self-narration is to establish temporal and causal connections between otherwise distinct, isolated autobiographical memories. Self-narratives lend narrative form to our personal past.

Autobiographical remembering (the process) and autobiographical memories (the resulting “building blocks”), Heersmink argues, are distributed across the brain, the rest of the body, and the local environment. This means that autobiographical remembering and its products importantly depends on resources in the environment, including artefacts and other agents. Yet, in describing self-narration, he is committed to Marya Schechtman’s influential narrative self-constitution view.

On this view, self-narration is governed by “implicit organising principles” of the mind. Whatever these are. In any case, self-narratives are at a remove from the agent’s embodied interaction with the socio-cultural environment. They can lend themselves to articulation and so communication, but that is not how the important self-narrative work gets done.

The narrative self-constitution view is committed to an individualistic and internalistic conception of the mind: mental phenomena, including self-narration, are realised by an individual agent without any significant reliance on embodied interactions with the local environment. There thus appears to be a disconnect between Heersmink’s understanding of autobiographical remembering as a thoroughly distributed process and self-narration as an individually and internally realised process.

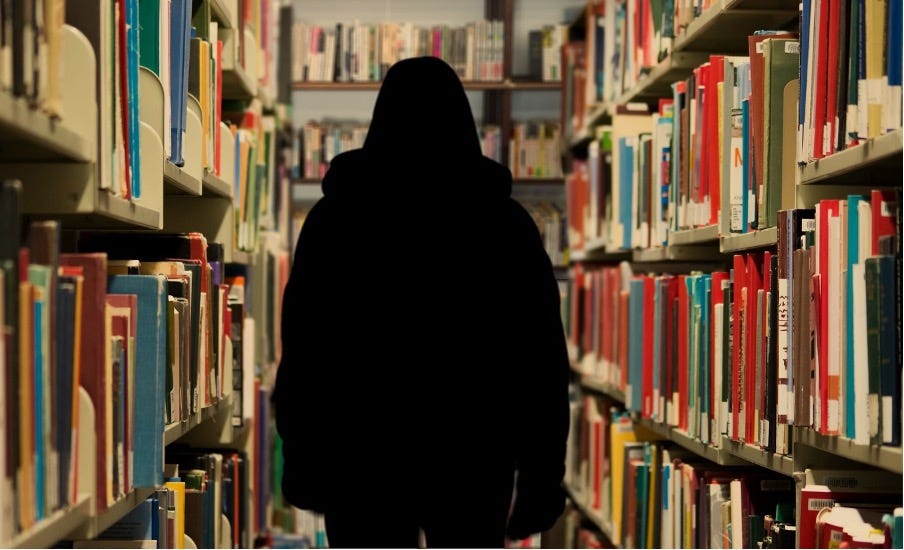

I propose a different account of the relationship between autobiographical remembering and self-narration. First, on my view, self-narration is distributed across the brain, the rest of the body, and the local environment. In a slogan: self-narrative is not something that we are, but something that we actively do.

It is something that we bring about through our embodied interactions with our socio-culturally shaped environment. In conversation and through various text-based narrative practices, including life writing, blogging, and social media posting. And, at times, through performance art, singer-songwriting, or the creation of comics, documentaries, photo series.

Second, I submit that the relationship between autobiographical memories and self-narratives is more complex and dynamical than the “building block” metaphor suggests. After all, autobiographical memories are not ready-made, static mental objects that can be used to build a stable “brick wall” of our own personal past. If anything, autobiographical memories should be understood as dynamical and constructive components that influence, and are influenced by, our practices of self-narration.

How we answer the question about the relationship between autobiographical remembering and self-narration has important consequences. The distributedness of autobiographical remembering and self-narration entails that our narrative accounts of our personal past are much more influenced by our socio-cultural environments than initially assumed. For better and for worse.

Consider master plots as one important case in point. Master plots shape our self-narratives and, by implication, our autobiographical rememberings. They are narrative templates that prescribe how events in a story ought to be structured and connected. These templates are shaped, across time, by the members of dominant groups in a given socio-cultural community.

Most of us grow up with rich traditions of storytelling, in which fairy tales, fables, myths, and community and family narratives abound. And most of us are exposed, on a regular basis, to various narratives that form part of the storytelling boom. Through our frequent engagement with these narratives, we become highly familiar with master plots. When we craft our self-narratives, we draw (often unintended) on this rich repository of master plots. Hilde Lindemann Nelson was probably the first philosopher identifying this important connection between master plots and self-narration.

Master plots provide a powerful means of manifesting and perpetuating dominant ideologies, for example sexism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, racism, classism, ableism, and their intersections. In other words, master plots lend form to narratives that easily conform with and reaffirm these dominant ideologies. They are representative of the experiences and expectations of the members of dominating groups.

Consequently, master plots are imposed upon self-narrators who belong to (often intersecting) structurally oppressed groups. By design, they do not capture the autobiographical rememberings and living conditions of agents who deviate from oppressive groups.

In many cases, self-narratives perpetuate and reinforce master plots. They thereby contribute, often unintendedly, to the upholding of oppressive ideologies. However, self-narrators who are members of structurally oppressed groups can actively resist master plots. They do this by establishing their own ways of configuring and conveying their personal past experiences through their distributed self-narrative practices. This form of narrative resistance then gives rise to counter narratives.

Over time, these manifestations of narrative resistance can solidify into counter plots, thus offering templates for self-narrators whose experiences and perspectives have been silenced by dominant ideologies. But note that counter plots always develop against the backdrop of master plots. This means that master plots can be resisted, but never fully escaped.

As an example, consider the following biographical master plot mentioned by Kate McLean and Moin Syed: “finishing school, finding a job, getting married, and having a child.” This master plot is still highly prevalent in the US and many other Western and Westernised societies. For female self-narrators, this master plot perpetuates, amongst other things, the ideology of pronatalism, which equates womanhood with motherhood.

Women whose biological-reproductive features would allow them to bear a child are structurally oppressed by the patriarchal ideology of womanhood-as-motherhood. (I note in passing that philosophical theorising on pronatalism does not consider the impact of pronatalism on transwomen and their self-narrative practices. This is in itself, I assume, an oversight owed to structural oppression.)

We don’t even have an adequate notion, at least in English-speaking communities, to refer to women who deviate from the patriarchal norm.“Voluntary childfree” women are depicted as enjoying freedoms that mothers don’t have; “voluntary childless” women are described as missing out on the riches of motherhood.

By design, pronatalist master plots don’t capture the remembered experiences of women who have decided to not procreate.

How can they remember their personal past and engage in self-narration? Without being considered as “free” or “less” relative to women-as-mothers? Without being seen as a “bitch,” a “witch,” or a “spinster”?

To address these questions through their self-narrative practices, concerned female self-narrators need to actively craft counter narratives. This example can illustrate how master plots, counter plots, self-narration, and autobiographical remembering are importantly related.

Master plots do not only prescribe how autobiographical memories ought to be connected in self-narrative form. They also prescribe which aspects of our personal pasts are considered to be narratable and sharable, given the norms and expectations that dominate in our socio-cultural communities.

If it is correct to assume, following Robyn Fivush’s proposal, that our self-narratives shape, to a considerable degree, how we remember our personal past, then master plots are very important indeed for our understanding of autobiographical remembering. Arguably, master plots shape, at least in part, how we remember our personal past across time, as we draft and revise our self-narratives through our active engagement in various narrative practices.

The upshot of my account of self-narration and autobiographical remembering now comes into view. Both processes are distributed across the brain, the rest of the body, and the socio-cultural environment. Both processes mutually constrain and enforce each other across time.

We can only tell what we can – or seem to – remember (if we set aside cases of lying and bullshitting). And what we tell, and how we tell it – and what we omit, smother, withdraw – influences how we will remember our personal past. These mnemonic-narrative loops are shaped by socio-cultural practices, expectations, and norms. Master plots, I have proposed, are one important case in point.

Self-narratives, all of this suggests, are never value- or context-free. They are always already situated in the context of ideologies of power and domination. This is true for the autobiographical narrative products in the attentional and emotional storytelling economy. It is also true for our everyday self-narrative conversations. Self-narratives can contribute to the perpetuation of structurally oppressive socio-cultural dynamics. This is their greatest peril. But they can also be empowering forms of resistance, transgression, and transformation. This is their greatest strength.