Disillusioned

A qualitative study of 220 former ISIS members found that while the most mentioned reasons for joining the group related to helping others and identity, such as being moved by news coverage of massacres to fight against the Assad regime, the most mentioned causes of disengagement or disillusionment with the group were internal problems: for instance, unfair enforcement of rules depending on one’s place in the hierarchy. That is, the reasons for entering were very different from the reasons for leaving, not just in content but in structure.

This is perhaps part of the difficulty in building effective deradicalization programs, or even dissuading yourself – if the best way to disengage is joining up and then finding out it wasn’t like you thought it would be, this can't be put into a curriculum or mental exercise. Joining and then leaving ISIS are of course actions that are caused by complex and unknown factors. But an aspect of the process, though perhaps not a causally significant one, is changes of mind. These participants – most of whom were not from the Levant – must have substantially changed their ways of thinking about questions ranging from how to live, who to trust, and what will happen next. And part of this story is disillusionment.

Could disillusionment work this way in general? That is, could it be that we discard ideas in a very different way than we acquire them? This is a question about the process, to which we’ll add a question about the states of mind.

I’m starting a project on the idea of “reversals” in learning, cases where we form a belief and then leave it behind. Deradicalization is a messy, large-scale instance of reversal learning, at least when we’re talking about the more common case of someone not born into a radical set of beliefs. Alongside this, we might also put joining and then leaving a religion, immigrating and then returning home, transitioning gender and then detransitioning – these are external life changes, but in many cases they bring along changes in belief. To vastly simplify, the person has an initial set of beliefs and values, changes to a new one, and then returns to something like the first set.

Do and can we ever go back to a way of thinking?

Could a set of beliefs, concepts, and cognitive habits be there where we left it — or is what seems like a return to old beliefs actually something else entirely? This is the state question.

The case I started with, kinds of reasons given for involvement and then disillusionment in ISIS, seems to indicate that while the final state may not be much like the initial state, there’s something about the process of disillusionment that is more akin to being pushed out than to being pulled by something new. If that’s true, we might think of the person sort of passively falling back into their old beliefs – presumably only possible if there are some old beliefs already there, in a sense. I’m not sure that’s the right way to think of it, but it is one place to start. The other way is to go all the way back to the most basic forms of reversals.

Smaller reversals

Reversal learning is one of the behaviors we’ve been studying the longest in other animals. In fear extinction paradigms, an animal learns a painful association, for instance between a sound and a shock. Then, they hear the sound with no shock often enough that they no longer show any fear response. The association is “extinguished” – but does that mean it’s gone?

Several types of behaviors show this isn’t typically the case: spontaneous recovery is when without any external change but just the passage of time, the animal will start displaying fear at the sound again. Reinstatement is when the shock alone brings back the fear of the sound. And reacquisition is when a new exposure to the sound and shock brings back the association, typically faster than it would for an animal who had not gone through the initial training and extinction phases.

Tronson et al (2012) ask a counterpart of the state question for this case in rodents: what kind of states do these processes of learning, unlearning, and relearning produce, and how similar are they to one another?

Linked to the process question, the finding that old learned connections are not undone but somehow linger has shown up in all kinds of learning contexts in humans and other animals. For instance, in the Morris water maze, where rats have to learn a location, then overwrite it with a new one, spontaneous recovery also occurs. This is more or less like when you learn one way to get to your favorite bookstore, they close and move to another location, you learn how to get there, and then one day you find yourself walking towards the old place again. Unlike fear extinction, this is not directly affective, emotional learning. And while some models describe fear learning as associative, navigation (at least the way rats do it) has a complex structure that we think of as a cognitive map.

Do these smaller reversals tell us something about disillusionment? They suggest to me that reversals at any scale are really their own kind of learning process, not to be thought of as just learning where we happen to retrace our steps. The ubiquity of spontaneous recovery, however, might make us turn the original question around: we started by wondering if it was possible to go back to a belief state you left and find it unchanged. But instead we could be asking: is it possible to get away from an old belief, and for how long?

The most extensive discussion of this idea in recent philosophy is in the “Spinozistic” theory of belief, which holds that beliefs are hard to discard and grab us very easily. In cognitive science, there’s also a lot of interest in the way in which “naive” or older theories can still influence our thinking when they are replaced by more sophisticated scientific ideas.

Both of these are concerned mainly with cases of linear learning, where we go on changing in the same direction and yet there is a sort of inertia from the past. But reversals force us to see these dynamics differently. On one side, in spontaneous recovery, we see the past as returning without any prompting. On the other side, in considering the states involved, it seems hard, perhaps impossible, to really return to the very same beliefs even if we wanted to.

Active and passive

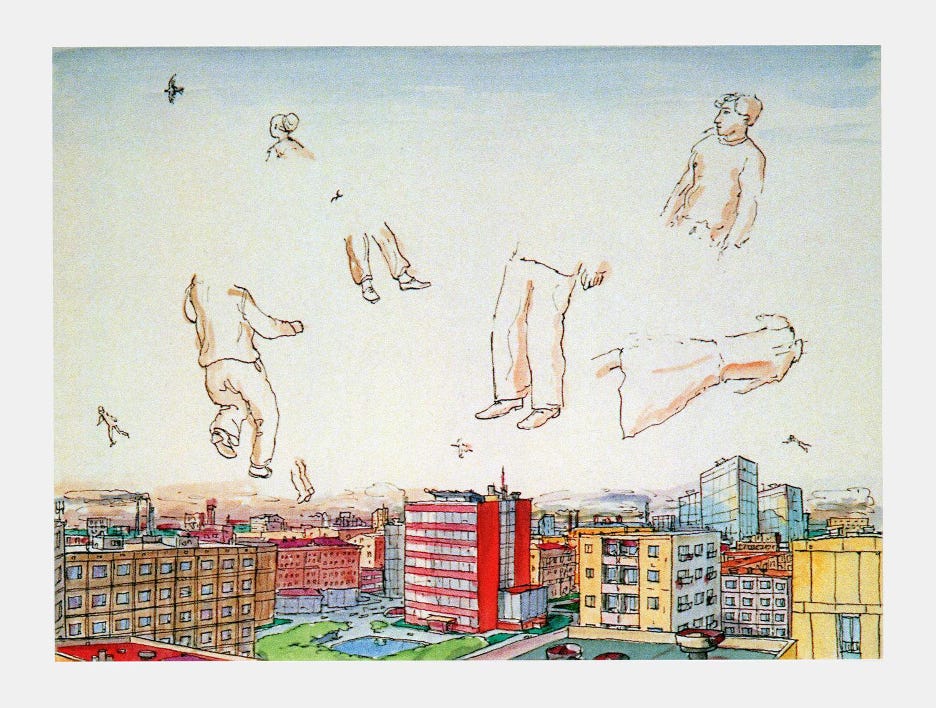

This drawing by Ilya Kabakov is part of a story “The Flying Komarov” where characters break away from normal life and float above the city. In it, he says that they sometimes enact scenes from life down below such as sitting down to tea on floating chairs. Like the return to old beliefs, is this return to an old habit a sort of passive reflex?

In this story, I think the answer is no. The floating people do these activities as a sort of joke, a way of reviving something, a gesture, or something else – they are not tied to these activities but glide like airplanes, become giant, enjoy floating while disappearing various body parts and finally, dissolve.

Without the explanation of habit or reflex, we have to wonder why some of them occasionally repeat bits of their old life below, among everything else.

Putting these pieces together, I have a sense that however we can re-utilize past ideas, concepts, and images in a reversal might be better thought of as an active feature of our cognition rather than a passive, and perhaps even unfortunate, difficulty in leaving things behind.

Hypothetically, a creature could have no capacity for reversal learning at all: she would still be able to learn A, then not A, then A again, but for her, the third stage would be just like learning A anew. Rats and humans, at least, don’t seem to be like this. My starting point, in trying to figure out the nature of this reversal capacity, is that the past does not return by itself but rather we reach back to it, imperfectly, and at times, without meaning or fully wanting to.

1.Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. D. (2020). ISIS in their own words. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(1), 82-127.

2. Tronson, N. C., Corcoran, K. A., Jovasevic, V., & Radulovic, J. (2012). Fear conditioning and extinction: emotional states encoded by distinct signaling pathways. Trends in neurosciences, 35(3), 145–155.

3. Mandelbaum, E. (2014). Thinking is believing. Inquiry, 57(1), 55-96.

4. Shtulman, A., & Legare, C. H. (2020). Competing explanations of competing explanations: Accounting for conflict between scientific and folk explanations. Topics in cognitive science, 12(4), 1337-1362.